The North

American Free Trade Agreement

January 1999

Implementation of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) began on Jan. 1, 1994. This agreement will remove most barriers to trade and investment among the United States, Canada, and Mexico.

Under the NAFTA, all nontariff barriers to agricultural trade between the United States and Mexico were eliminated. In addition, many tariffs were eliminated immediately, with others being phased out over periods of 5 to 15 years. All agricultural provisions will be implemented by the year 2008. For import-sensitive industries, long transition periods and special safeguards will allow for an orderly adjustment to free trade with Mexico.

The agricultural provisions of the U.S.-Canada Free Trade Agreement (FTA), in effect since 1989, were incorporated into the NAFTA. Under these provisions, all tariffs affecting agricultural trade between the United States and Canada, with a few exceptions for items covered by tariff-rate quotas (TRQ’s), were removed before Jan. 1, 1998.

Mexico and Canada reached a separate bilateral NAFTA agreement on market access for agricultural products. The Mexican-Canadian agreement eliminated most tariffs either immediately or over 5, 10, or 15 years. Tariffs between the two countries affecting trade in dairy, poultry, eggs, and sugar are maintained.

Benefits to U.S. Agriculture: Canada and Mexico are, respectively, the second and third largest export markets for U.S. agricultural products. Exports to the two markets combined are greater than exports to Japan or the 15-member European Union. In fiscal year 1998 (October-September), nearly one out of every four dollars earned through U.S. agricultural exports was earned in North America.

From fiscal year (FY) 1992-98, the value of U.S. agricultural exports worldwide climbed 26 percent. Over that same period, U.S. farm and food exports to our two NAFTA markets grew by 48 percent. In FY 1998, U.S. farmers, food processors, and exporters shipped nearly $249 million worth of agricultural products to Canada and Mexico a week. This is an increase of $135 million a week and $7.0 billion a year compared with what they shipped, on average, during the four years prior to NAFTA.

Trade with Mexico: From fiscal year 1997 to 1998, U.S. farm and food exports to Mexico climbed by $881 million to $5.9 billion -- the highest level ever and the fourth record in 5 years under NAFTA. U.S. exports of soybeans, cotton, and rice all set new records. By value, more U.S. agricultural products went to Mexico last year than to China, Hong Kong, and Russia combined.

In the years immediately prior to NAFTA, U.S. agricultural products lost market share in Mexico as competition for the Mexican market increased. NAFTA reversed this trend. The United States now supplies more than 75 percent of Mexico’s total agricultural imports, due in part to the price advantage and preferential access that U.S. products now enjoy. For example, Mexico’s imports of U.S. red meat and poultry have grown rapidly, exceeding pre-NAFTA levels and reaching the highest level ever in FY 1998.

NAFTA kept Mexican markets open to U.S. farm and food products despite the worst economic crisis in Mexico’s modern history. In the wake of the peso devaluation and its aftermath, U.S. agricultural exports dropped by only 11 percent in FY 1995, and have since surged back with a 60-percent gain in FY 1998. NAFTA cushioned the downturn and helped speed the recovery because of preferential access for U.S. products. In fact, rather than raising import barriers in response to its economic problems, Mexico adhered to NAFTA commitments and continued to reduce tariffs.

January 1998 marked the fifth round of tariff cuts under NAFTA, further opening the market to U.S. products. U.S. commodities now eligible for duty-free access under Mexico’s NAFTA TRQ’s, include U.S. corn, dried beans, poultry, animal fats, barley, eggs, and potatoes. All tariffs are to be eliminated by 2008.

Although agricultural trade has increased in both directions under NAFTA, U.S. exports to Mexico have increased faster than imports from Mexico. The U.S. agricultural trade surplus with Mexico was $1.32 billion in FY 1998.

Trade with Canada: Canada has been a steadily growing market for U.S. agriculture under the FTA, with U.S. farm and food exports increasing an average of nearly 10 percent a year from FY 1990-98. U.S. exports reached a record $7.0 billion to Canada in FY 1998, an increase of more than 89 percent since FY 1990. Fresh and processed fruits and vegetables, snacks foods, and other consumer foods account for close to three-fourths of U.S. sales.

U.S. exports of bulk, intermediate, and consumer-oriented products to Canada all set records in FY 1998, with new value highs for coarse grains, rice, vegetable oils, feeds and fodders, planting seeds, snack foods, breakfast cereals, red meats, poultry meat, dairy products, eggs and products, fresh and processed vegetables and vegetable juices, processed fruits and fruit juices, and several other product categories.

Before the 1989 FTA with Canada, U.S. products generally accounted for less than 60 percent of total Canadian agricultural imports. U.S. products now make up around two-thirds of total import value, as the U.S. share has trended upward at the expense of other suppliers because of lower tariffs and preferential U.S. access under the FTA/NAFTA. With a few exceptions, tariffs not already eliminated dropped to zero on Jan. 1, 1998.

In 1996, the first NAFTA dispute settlement panel reviewed the higher tariffs Canada is applying to its dairy, poultry, egg, barley, and margarine products, which were previously subject to nontariff barriers before implementation of the Uruguay Round. The panel ruled that Canada’s tariff-rate quotas are consistent with NAFTA, and thus do not have to be eliminated.

NAFTA Eliminates Trade Barriers: Under NAFTA, all nontariff measures affecting agricultural trade between the United States and Mexico were eliminated on Jan. 1, 1994. These barriers -- including Mexico’s import licensing system (which had been the largest single barrier to U.S. agricultural sales) -- were converted to either tariff-rate quotas or ordinary tariffs.

All agricultural tariffs between Mexico and the United States will be eliminated. Many were immediately eliminated and others will be phased out over transition periods of 5, 10, or 15 years. The immediate tariff eliminations applied to a broad range of agricultural products. In fact, more than half the value of agricultural trade became duty free when the agreement went into effect. Tariff reductions between the United States and Canada had already been implemented under the U.S.-Canada FTA.

Both Mexico and the United States protected their import-sensitive sectors with longer transition periods, tariff-rate quotas, and, for certain products, special safeguard provisions. However, once the 15-year transition period has passed, free trade with Mexico will prevail for all agricultural products. NAFTA also provides for tough rules of origin to ensure that maximum benefits accrue only to those items produced in North America.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities

To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, Room 326-W, Whitten Building, 14th and Independence Avenue, SW, Washington DC 20250-9410 or call (202) 720-5964 (voice or TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer

DID YOU KNOW ?

Over 2,350 operations in the Mexican Maquiladoras

produce product, primarily for

export. These operations employ 1,000,000 Mexican

workers at extremely low wages. Employment in the Mexican Maquiladoras

has increased by approximately 100% since 1993. Companies in 20 different

countries use the Mexican Maquiladoras to exploit Mexican workers and gain

access to the U.S. and Canadian markets with little or no regulation or

control. These countries include: Japan, Korea, China, Taiwan, England,

France, and others.

Reality for Maquiladora Workers

Workers and families live in shacks built from scraps

of wood and metal with dirt

floors. Hundreds of thousands of shacks along dirt

roads with deep ruts and standing water Sewage flowing along open ditches.

Conveniently beyond the view of the modern industrial parks and their corporate

visitors.

Companies exploiting workers and their environment.

Poverty wages paid by huge multinational corporations. Non- existent application

of safety or environmental standards. Mental, physical and sometimes sexual

abuse

These are NOT refugee families fleeing famine, war,

or political oppression.

This is NOT a situation that the rich multi-national

companies cannot afford decent wages paid in other facilities across the

border,

Huge savings generated are NOT being used to lower

the cost of their

products.

These ARE workers who labor each day in a modern

factory for many of

the same employers as workers in the U.S.

Employers ARE fleeing to the Mexican Maquiladoras

from the U.S. and

other countries to exploit Mexican workers and

their environment.

Companies ARE hoarding the savings generated from

their exploitation

for higher and higher corporate profits.

TOP TEN NAFTA ABUSERS

1.GENERAL MOTORS CORPORATION, INCLUDING DELPHI AND

DELCO

2.ZENITH ELECTRONICS CORPORATION

3.UNITED TECHNOLOGIES

4.ALCOA FUJIKURA LTD.

5.LEAR SEATING CORPORATION

6.YAZAKI NORTH AMERICA

7.CHRYSLER CORPORATION

8.THOMSON CONSUMER ELECTRONICS

9.SONY CORPORATION OF AMERICA

10.FORD MOTOR COMPANY

Top ten lists are based upon the number of workers employed in the Mexican Maquildoras.

For additional information regarding trade related

issues contact:

United Steelworkers of America, Fair Trade Watch,

Five Gateway Center Pittsburgh, PA 15222 www.uswa.org

MAI: Wonnemonat für das Kapital - www.oneworld.at

Unter Ausschluß der Öffentlichkeit bereitete die OECD ein Abkommen zum Schutz ausländischer Investitionen vor, das nationale Regierungen noch stärker dem internationalen Kapital ausliefert.

Wir schreiben die Verfassung des globalen Marktes", sprach Renato Ruggiero, der Präsident der Welthandelshandelsorganisation (WTO). Diese ökonomistische Allmachtsphantasie wird seit Mai 1995 in der OECD ausverhandelt. Ziel dieses "Multilateral Agreement on Investment" (MAI) ist die Liberalisierung und der Schutz ausländischer Investitionen. Die Einhaltung der MAI-Prinzipien kann von multinationalen Unternehmen eingeklagt werden, und die Staaten haben sich an das Urteil eines im MAI vorgesehenen Schiedsgerichtes zu halten. Die Bestimmungen dieses geplanten Ab-kommens stellen nach Ansicht seiner Kritikerlnnen eine neoliberale Verschärfung und Ausdehnung der NAFTA-Bestimmungen über den ganzen Globus dar.

Kritisiert wird von US-amerikanischen und kanadischen NG0s, daß die Verhandlungen bislang fernab jeder Öffentlichkeit erfolgten und daß die Machtverschiebung zugunsten multinationaler Unternehmen und ihre Auswirkungen politisch nicht diskutiert werden. Das MAI soll im Mai 1998 unterzeichnet werden. Die unterzeichnenden Staaten verpflichten sich, für mindestens 20 Jahre die Bestimmungen des MAI zum Schutz internationaler Investitionen einzuhalten. Laut OECD ist das MAI "der erste Versuch, in ei-nem internationalen Abkommen multilaterale Verpflichtungen zu schaffen, welche den Schutz von Investitionen, die Liberalisierung von Investitionen und verpflich-tende Streitbeilegungsmechanismen kom-biniert". Es zielt auf die "Eliminierung von Rahmenbedingungen, welche internationale Investitionsflüsse stören könnten." Die ausländischen Investoren sollen zumindest "nationale Behandlung" (Gleich-stellung mit inländischen Unternehmen) und einen" Meistbegünstigtenstatus" genießen. Da "Investitionen" vom MAI extrem weit definiert werden - u. a. auch geistiges Eigentum, Grundstücke, indirekte (speku-lative) Investitionen -, wird nahezu die gesamte Ökonomie eines Landes prinzipiell von den MAI-Bestimmungen erfaßt.

Entstehungshintergrund des MAI ist der Versuch vor allem der USA, im Interesse ihrer Konzerne die regulativen Möglichkeiten von Regierungen zu beschränken (z. B. Verpflichtung zu einem Mindestanteil von einheimischen Beschäftigten, zur einheimischen Vorproduktion, Regulationen von Gewinn- und Kapitaltransfers usw.). Weiters soll eine Öffnung von geschlossenen oder regulierten Märkten erzwungen

werden, was im Falle der Länder der südlichen Hemisphäre nicht durchgehend über die Strukturanpassungsreformen von IWF und Weltbank zu bewerkstelligen war.

Um eine Verwässerung des neoliberalen Entwurfes zu vermeiden, verhandeln nur die 29 reichsten Industrienationen (unter Beobachtung u. a. von IWF und WTO). Andere Staaten können und sollen laut OECD dem Vertragswerk beitreten, allerdings dann zu den bereits festgelegten Bedingungen. Die Nicht-OECD-Länder befinden sich da-bei in einem Dilemma: Einerseits wollen sie ausländische Investitionen anziehen (was ihnen schwerer gemacht wird, wenn sie sich nicht den Bedingungen des MAI unterwerfen), andererseits verzichten sie durch den Beitritt auf wichtige Instrumente, um regulierend eingreifen zu können. Eine kritische Analyse der Entwürfe sowie eine öffentliche Diskussion über das Vertragswerk, welches Staaten unabhängig vom politischen Willen seiner Bürgerlnnen 20 Jahre lang bindet, fehlen bislang.

von Bernhard Mark-Ungericht

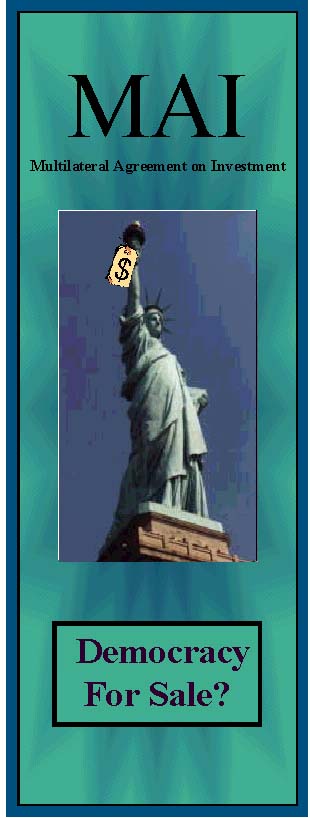

It's the Multilateral Agreement

on Investment (MAI), an agreement under negotiation in Paris behind

closed doors since 1995

by 29 of the wealthy nations that make up the Organization for Economic

Cooperation and Development

(OECD).

If the targeted completion

date of late spring 1998 is met, the MAI could come to the Senate for

ratification as a treaty

as early as the summer of 1998.

WHY HAVE YOU NEVER HEARD OF IT?

Because MAI policymakers

in the Clinton Administration don't think the public needs to know.

Apparently they don't think

Congress needs to know either, since America's elected representatives

have

been kept in the dark too,

even though the text of the agreement is almost final.

But the world's major corporations

know about it--and they like it a lot. The U.S. Council for

International Business and

other corporate lobbies have been consulted regularly and are actively

involved in developing the

MAI. Meanwhile, non-governmental labor, environmental and community

organizations have been

largely shut out.

WHY YOU SHOULD KNOW ABOUT

IT

The MAI is designed to multiply

the power of corporations over governments and eliminate policies that

could restrict the movement

of factories and money around the world. It places corporate profits above

all other values. If enacted

in its current form, the MAI would radically limit our ability to promote

social, economic and environmental

justice. In other words, it puts our democracy at risk.

This is why the MAI is being

strongly resisted by people around the globe. Citizens' and indigenous

movements are rallying against

the MAI in North America, Europe, Africa, Asia and Latin America.

The MAI tramples on our

democracy by empowering foreign corporations to sue governments directly

for cash compensation for

failure to enforce the MAI. Taxpayers would be required to pick up the

tab.

WHAT WOULD THE MAI DO?

The MAI would set strongly

enforced global rules limiting governments' right and ability to regulate

foreign investors and corporations.

Specifically, it would...

Empower foreign corporations

to sue the federal government over federal, state and local laws,

which could force governments

to pay damages and/or overturn their laws. (Investor to State

Dispute Settlement)

Require governments, as a

result of binding arbitration, to compensate foreign corporations for laws

that could limit corporate

profits, such as environment, human rights, labor, public health,

consumer protection and

local community development standards. Believe it or not, this would

even apply to government

policies that could limit future profits. (Establishes a global "regulatory

takings" law.)

Prevent governments from

promoting local businesses by requiring that foreign corporations be

treated at least as favorably

as domestic companies. Foreign corporations could be treated better

than domestic companies,

however. (National Treatment)

Require countries to treat

investors from any country in the same manner, preventing any country

or state from using human

rights, labor or environmental standards as investment criteria. (Most

Favored Nation)

Keep governments from requiring

foreign corporations to meet certain conditions, such as

maintaining an investment

in a community for a set amount of time, using recycled or domestic

content in manufacturing,

or hiring local workers even if the same requirements are applied to

domestic investments. (Performance

Requirements)

IT'S A BAD DEAL FOR WORKING PEOPLE

The MAI would establish and

consolidate extensive rights for investors and corporations while

limiting existing protections

for labor. As a result, the standard of living and the rights of working

people in the United States

and worldwide would be threatened in a number of ways. Here are a few:

Foreign corporations would

be exempt from many national, state and local initiatives that promote

local employment and investments

because the MAI bans performance standards and other policies

that target specific kinds

of development such as small business.

No one would be able to

require foreign firms to hire a certain percentage of local residents.

They

could not be required to

use domestic materials, which creates local jobs.

The MAI makes it easier

for corporations to move capital where and when it is most profitable

with little accountability.

This would accelerate plant closings and job loss in the U.S. as

corporations seek lower

wages and labor standards, especially as developing countries are

pressured into signing the

MAI.

As NAFTA has already shown,

corporations can use the threat of moving to other countries to

diminish union organizing

and power. The MAI would dramatically increase their ability to use this

threat.

IT'S AN ENVIRONMENTAL

HAZARD

The MAI would pose an immediate

threat to environmental protection. Regulating business operations is

vital to controlling environmental

damage. The gravest threat to government's power to regulate is in the

MAI's provisions on expropriation

and the ability of foreign corporations to sue governments if policies

undermine planned profits.

By allowing foreign corporations

to challenge environmental and health regulations in special "corporate

courts," the MAI would arm

investors to attack existing policies or to discourage future government

actions for a safe and healthy

environment. Here's how:

TOXICS: If the MAI becomes

law, many federal, state and local laws governing toxics would be

endangered. Foreign companies

could claim that the value of their investments would decline due to

policies restricting toxic

emissions or disposal practices. As in the Ethyl case cited above, investors

are

already trying to intimidate

governments and forestall regulation by suing for huge sums.

PROCUREMENT: Federal, state

and local governments are at last beginning to introduce social

concerns into how they spend

taxpayers' money. An executive order directs federal agencies to buy

"green" products, such as

those made with recycled content or using renewable energy. Cities and

counties are moving in this

direction too. These good efforts would run afoul of the MAI which would

ban any performance requirements,

for instance offering priority to companies using best environmental

practices.

SUSTAINABILITY and NATURAL

RESOURCES: The MAI clashes with the move towards a more

sustainable future, which

many believe should be built on small-scale enterprises and local control

of

resources. The MAI would

also guarantee large multinational corporations with new rights to establish

mining, timber or other

natural resource-exploiting investments. The MAI could be used to overcome

moratoria on such destructive

activities. The planet simply cannot afford to be bound by the MAI's rules

for twenty years.

IT'S HARDER ON WOMEN

Despite important gains over

the past few decades, women continue to suffer discrimination worldwide,

with women of color and

poor women most affected. In 1995, nearly one quarter (24 percent) of all

women in the U.S. lived

below the poverty line, as compared to 18 percent of men. Also in the U.S.,

women's wages still average

only 70 percent of men's pay.

Policies designed to address

women's poverty and inequality would be directly attacked by the MAI.

Here's how:

Performance requirements,

such as requiring equal pay for equal work and laws requiring that a

certain percentage of employees

be women, would be forbidden under the MAI.

The MAI's national treatment

provision means that any subsidies, aid, credit programs or grants

targeted to women could

be considered discriminatory unless such benefits are also offered to

foreign investors.

This could deal a serious

blow to women-owned businesses in the U.S. and worldwide, including those

supported by micro-enterprise

programs that enable poor women, particularly former welfare recipients,

to become self sufficient.

Already, women-owned businesses in the U.S. are discriminated against in

credit markets and in procurement

contracts, despite the fact that they are the fastest growing sector of

the U.S. small business

community and employ large numbers of workers. Women's access to and

control over productive

resources would be reduced, not increased, by the MAI.

Small and women-owned businesses

would be forced into unfair and unwinnable competition with

giant foreign corporations

because of the MAI's overall goal of boosting the capacity of those

corporations to compete

in local markets.

The MAI would hurt all labor

unions, but would particularly undermine union women who are

playing an increasingly

active role in unions. Good wages, benefits for themselves and their

families, and job security

are particularly critical for women, who are concentrated in the service

sector, with its low wages

and poor benefits, and in industries with high health hazards and

exploitative working conditions,

such as garments and chicken processing. New welfare laws are

increasing the number of

low-skilled women entering these jobs.

IT'S AN ASSAULT ON HUMAN RIGHTS

A fundamental objective of

the MAI is to erect a firewall between economic and social policy. Many

multinational corporations

vehemently oppose the use of economic sanctions to force compliance with

human rights, labor and

environmental standards that might affect their bottom line. Nor do they

want to

be held directly accountable

for their business relationships with governments that systematically violate

these standards.

The MAI would not allow the

Massachusetts law that says no government agency may purchase

from a company that does

business in Burma or any similar law aimed at restricting government

purchases that violate human

rights.

Had the MAI been in effect

during the 1980s and early 1990s, many of the investment sanctions

aimed at abolishing apartheid

in South Africa would have been forbidden. Nelson Mandela might

still be in prison.

In response to Royal Dutch/Shell's

environmental destruction and link to murders of activists in

Oganiland Nigeria, some

U.S. communities created "Shell-free" zones that banned investment by

Royal Dutch/Shell and its

subsidiaries. This would have violated the MAI's requirement that all

countries receive "most

favored nation" treatment.

More recently, some states

in the U.S. announced that they will divest from Swiss banks to protest

the World War II collaboration

between Swiss financial institutions and the Nazis. Under the MAI's

twisted value system, commercial

interests are more important than human rights, and so such a

censure would be out of

bounds.

IT'S AN AFFRONT TO GLOBAL JUSTICE

The MAI is the final pillar

of a system designed to promote unregulated economic globalization, where

values of the marketplace

have precedence over values of social and economic justice.

The goal of the MAI is to

eliminate policies that countries, especially developing countries, use

to protect

and direct their own resources

for the benefit of their own economies. These include laws regulating the

movement of capital across

their borders. Chile, for instance, requires investors to stay in certain

high-risk portfolios for

at least six months, as a means of slowing speculation and encouraging

investment

in productive activities.

This law would stand in direct conflict with the MAI.

Investors and OECD member

nations want to take the right to enact such policies away from developing

countries. This is why negotiations

were moved from the World Trade Organization, to which

developing countries belong

-- and where they had blocked earlier attempts to pass an MAI-like

agreement -- to the OECD,

where they are excluded. If and when the new rules are set, developing

countries will be told to

sign on the dotted line or lose needed foreign investment.

This is a direct assault

on the economic, social and democratic rights of citizens in non-OECD countries.

It is not new. In fact,

the MAI locks in place many of the economic policies that the IMF and the

World

Bank have imposed on over

90 countries in the past 15 years. Such harsh policies underlie international

trade pacts like WTO and

NAFTA.

Just like these other agreements,

the MAI would benefit investors over workers, corporations over

nations, the North over

the South, the well-to-do over the poor, men over women, short-term profit

and

efficiency over long-term

social and environmental sustainability, and free markets over free people.

IF NOT THE MAI, THEN WHAT?

In a February 1998 letter

to the OECD, over 600 civil society organizations from 68 countries declared

their opposition to the

MAI, citing the negative impacts of the agreement. They noted that the

MAI

conflicts with many widely-ratified

international treaties supporting human, social and cultural, economic

and political rights of

men, women and children.

But they also agreed that

international investments require regulation, given the scale of economic

instability and social and

environmental disruption created by the increasing mobility of capital.

So, if not the MAI, then

what? The answer is quite simple. We need an investment agreement that

is

fashioned with full citizen

participation and approval. We want an agreement that makes people's

economic, environmental

and social priorities the tail that wags the global investment dog. And

we want

an agreement that holds

multinational corporations and investors accountable to these citizen-defined

priorities.

Such an agreement would

be far different from the MAI, which promotes corporate greed disguised

as

investor rights.

Among the demands made by

the 600-plus citizen's groups are that the OECD and its member countries

take the following actions:

1.Immediately suspend negotiations,

and undertake, with meaningful public input and participation,

an independent and comprehensive

assessment of the social, environmental, and development

impact of the MAI.

2.Require, in any final investment

agreement, that multinational investors be made to observe binding

agreements incorporating

environment, labor, health, safety and human rights standards to ensure

that they do not use the

MAI to exploit weak regulatory regimes.

3.Eliminate the investor/state

dispute resolution mechanism and put into place democratic and

transparent mechanisms that

ensure that civil society, including local and indigenous peoples, gain

new powers to hold investors

accountable.

4.Eliminate the MAI's expropriation

provision so that investors are not granted compensation for a

vague, broad notion of regulatory

takings. Governments must ensure that they do not have to pay

for the right to set environmental,

labor, health and safety standards, even if compliance with such

regulations imposes significant

financial obligations on investors.

5.Open the negotiation process

to citizens, which will require, among other things, timely public

release of draft texts and

country positions and the scheduling of open public meetings and hearings

in member and nonmember

countries.

6.Broaden government representation

at negotiations beyond state, commerce and finance agencies

to a broader range of government

agencies, ministries and parliamentary committees. (For instance,

health, education, economic

development, women's, labor, and environment agencies and

ministries.)

7.Make provisions for a country's

rapid withdrawal from the MAI when it deems this to be in the

best interest of its citizens.

WHAT YOU CAN DO

Now is the time to stop the

MAI and send a message to policymakers that we will not allow our

democracy - and our right

to shape the global economic policies that affect us - to be sold to the

highest

corporate bidder. Now is

the time to stand with men and women around the world as they fight for

the

same rights. By standing

together we can win!

Now is the time to:

MAKE NOISE!

THAT'S THE ONLY WAY WE CAN BE HEARD!

CONTACTS

Contact the following organizations

for more information about how you can get involved:

Alliance for Democracy:

David Lewit, 617-266-8687 <dlewit@igc.org> or Ruth Caplan

202-244-0561<rcaplan@igc.org>

Democratic Socialists of

America: Chris Riddiough 202-726-0745 <criddiough@dsausa>

Friends of the Earth: Andrea

Durbin <adurbin@foe.org> or Mark Vallianatos <mvalli@aol.com>

202-783-7400

Public Citizen's Global

Trade Watch: Chantell Taylor, 202-546-4996, x303 <ctaylor@citizen.org>

Sierra Club: Dan Seligman,

202-675-2387<dan.seligman@sierraclub.org>

50 Years Is Enough: Lisa

McGowan, 202-879-3187 <wb50yrs@igc.org>

Written materials:

The Multilateral Agreement

on Investment and the Threat to American Freedom, by Tony Clarke and

Maude Barlow, Stoddart Publishers,

Canada, March 1998, $9.95. Distributed in the USA by The Apex

Press (800-316-APEX)

Multilateral Agreement on

Investment: Potential Effects on State & Local Government, Western

Governors' Association,

April 1997

MAI websites:

Public Citizen's Global

Trade Watch. Wealth of information including complete MAI text.

http://www.citizen.org/pctrade/mai.html

Friends of the Earth - US.

Information includes potential environmental impacts.

http://www.foe.org/ga/mai.html

Preamble Center for Public

Policy. In-depth analysis of agreement.

http://www.rtk.net:80/preamble/mai/maihome.html

Island Centre for Community

Initiatives and National Centre for Sustainability in Canada. Articles,

updates, pros & cons,

good links.

http://www.islandnet.com/~ncfs/maisite

Ontario Public Interest

Research Group. Good information on what is happening.

http://www.flora.org/mai-not

aus: Umweltlexikon - www.katalyse.de